Conversations with Myself

-

2021 04 10–2021 07 04

-

During open hours

-

Exhibition

-

With visitor ticket

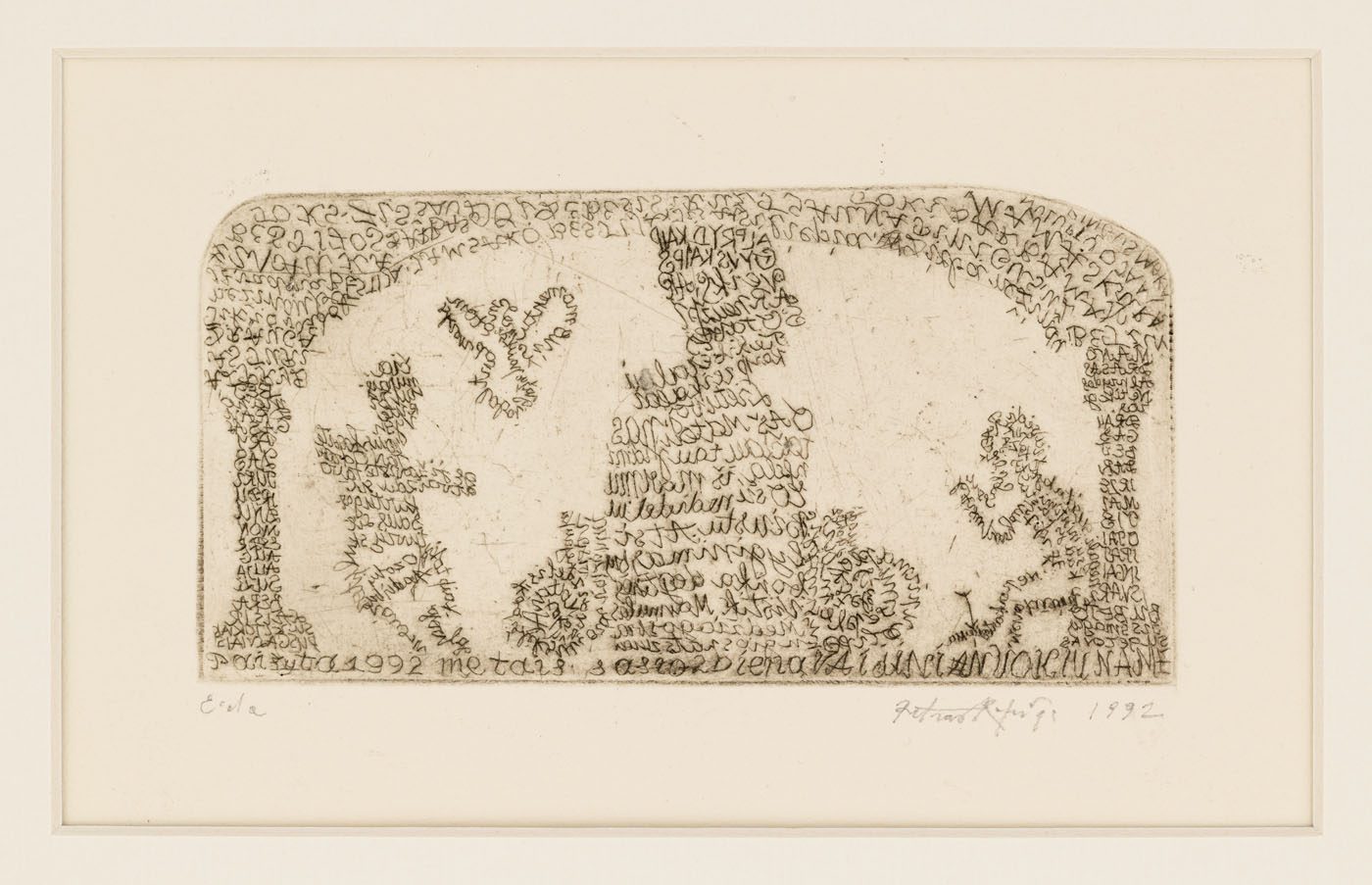

Petras Repšys is one of the most famous and popular Lithuanian contemporary artists, and a national art classic. His works encompass expression of a free temperamental personality, a passionate curiosity for history (of his own country, first of all), and a talent to generate images, translating it all into the language of art. A graphic artist, Repšys has observed how image follows the word and vice versa since the start of his creative life, and has contemplated this relationship between image and word in a variety of his art works.

Exhibition shows fifty-seven of Repšys’ etchings from cycles such as “Diary”, “Improvisations”, “A Conversation with Myself in Denmark” and “Finnish Sketches”. An amalgam of image and text forms their content and meaning. These engravings arouse curiosity of the most naïve kid and the most sophisticated intellectual. Discovering the surrounding environment through the medium of his sharp vision, the painter instantly registers everything that could possibly feed his imagination. According to Repšys, both wonderful and horrible things happen at the same time: one might be reading a book while at the same time a killing could be happening behind the wall. This simultaneous play of being in Repšys’ creations immerses the viewers into the world of his creation. It can be perceived as an imagination feeding adventure but also can be associated with various phenomena of contemporary culture ranging from “linguistic turn” to concrete poetry. Asked why he creates the images from words or why he creates texts to go parallel to drawn or engraved images, the artist shuns the question by saying that happens against his will, because when he sees no images in his mind, he tries to attract them by describing in words that which surrounds him.

According to Repšys, humans group around to language and tongue. His native language is Lithuanian, which today is spoken by a diminishing number of people. According to Repšys, it is necessary to create written monuments in order for Lithuanian language to survive. Even better if these monuments contain images that illustrate text and expand its meaning, giving additional dimensions and a sort of universality, because the images can be read universally, even by somebody who doesn’t understand Lithuanian language.